Wealth creation, however, depends on a minimum level of circulating capital to grow value through productivity-enhancing investment in industrial assets and new technologies, and this circulating capital in turn enables the accumulation of wealth for generational progression for recycling from fading to growing industries and for investment to address the chronic underfunding of, among other things, the national security that underpins our prosperity.

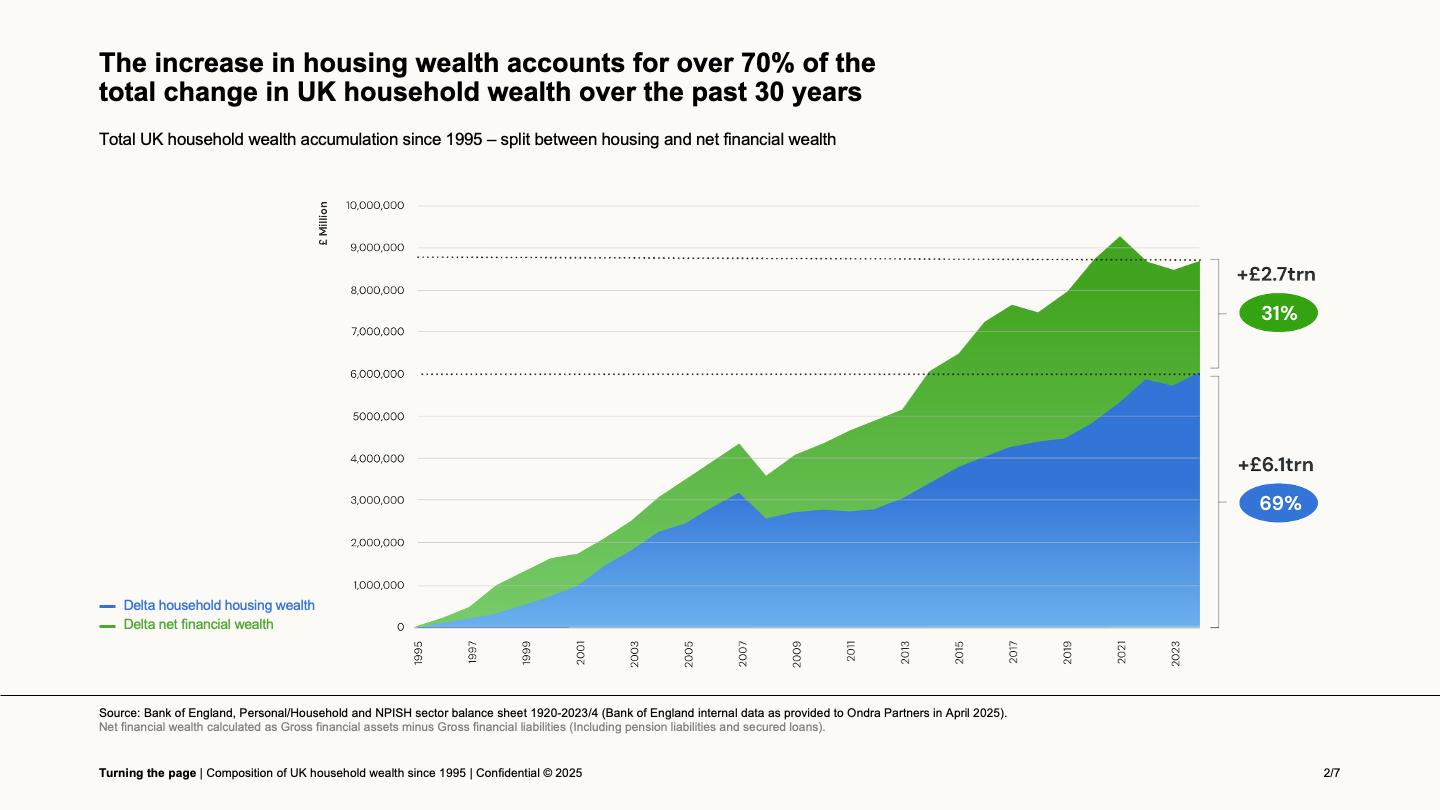

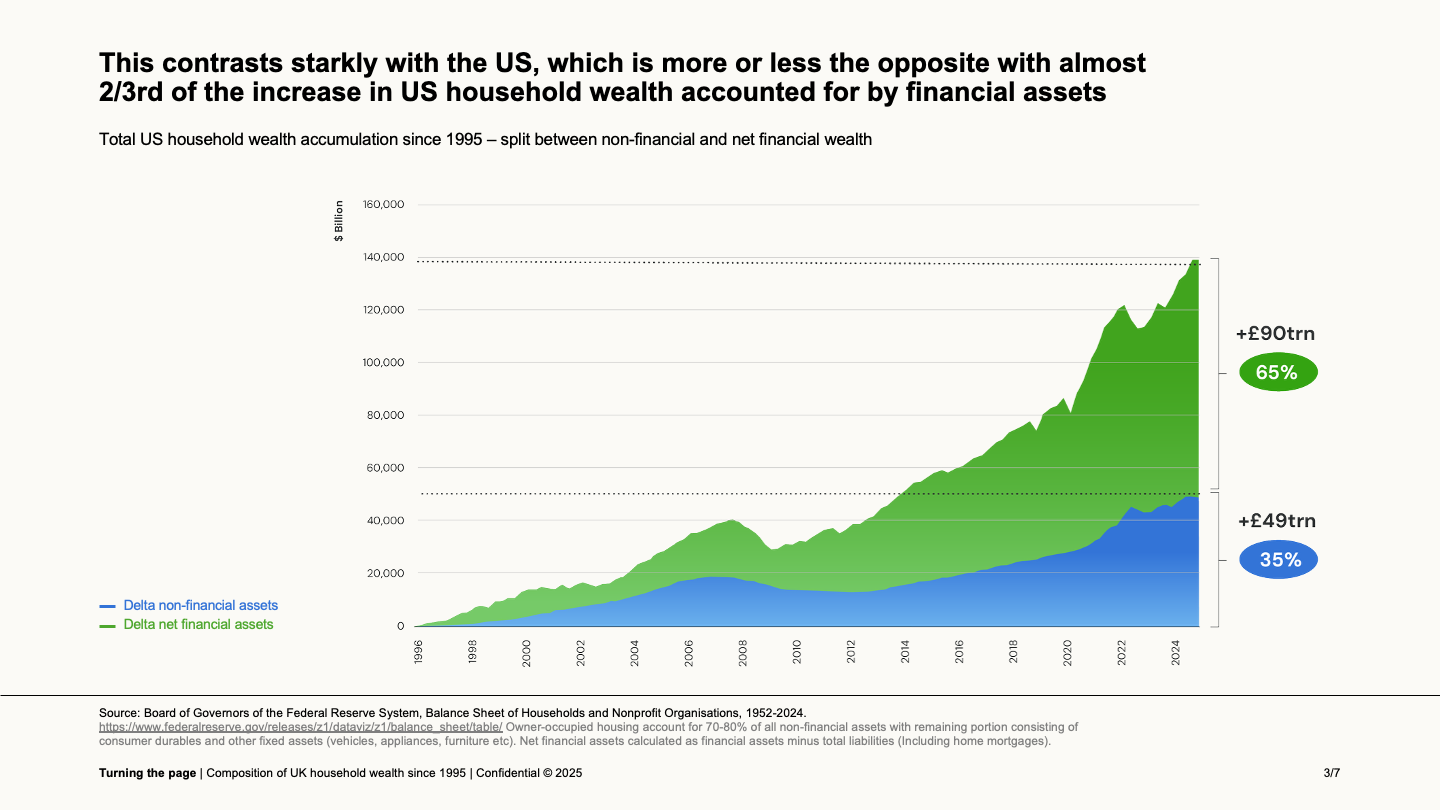

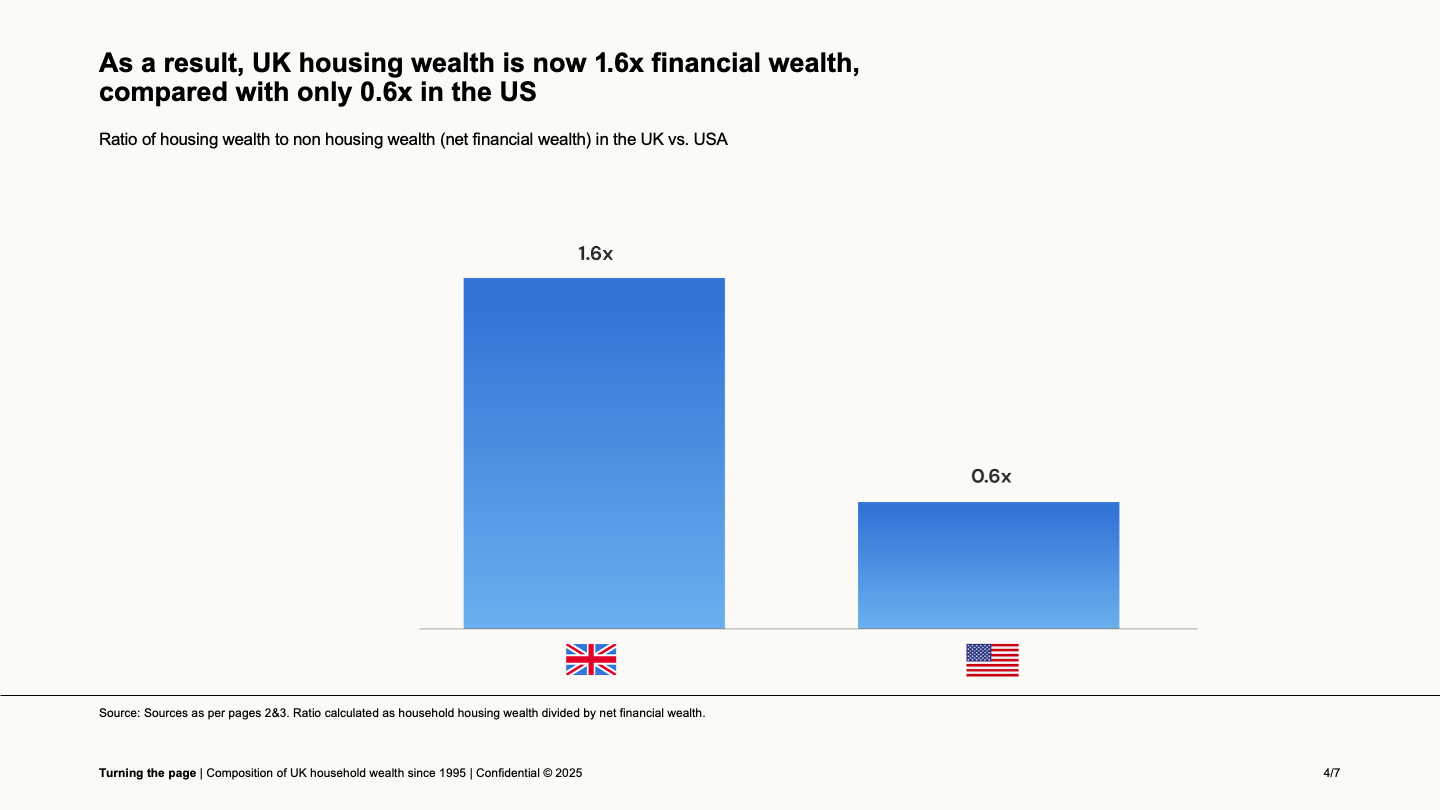

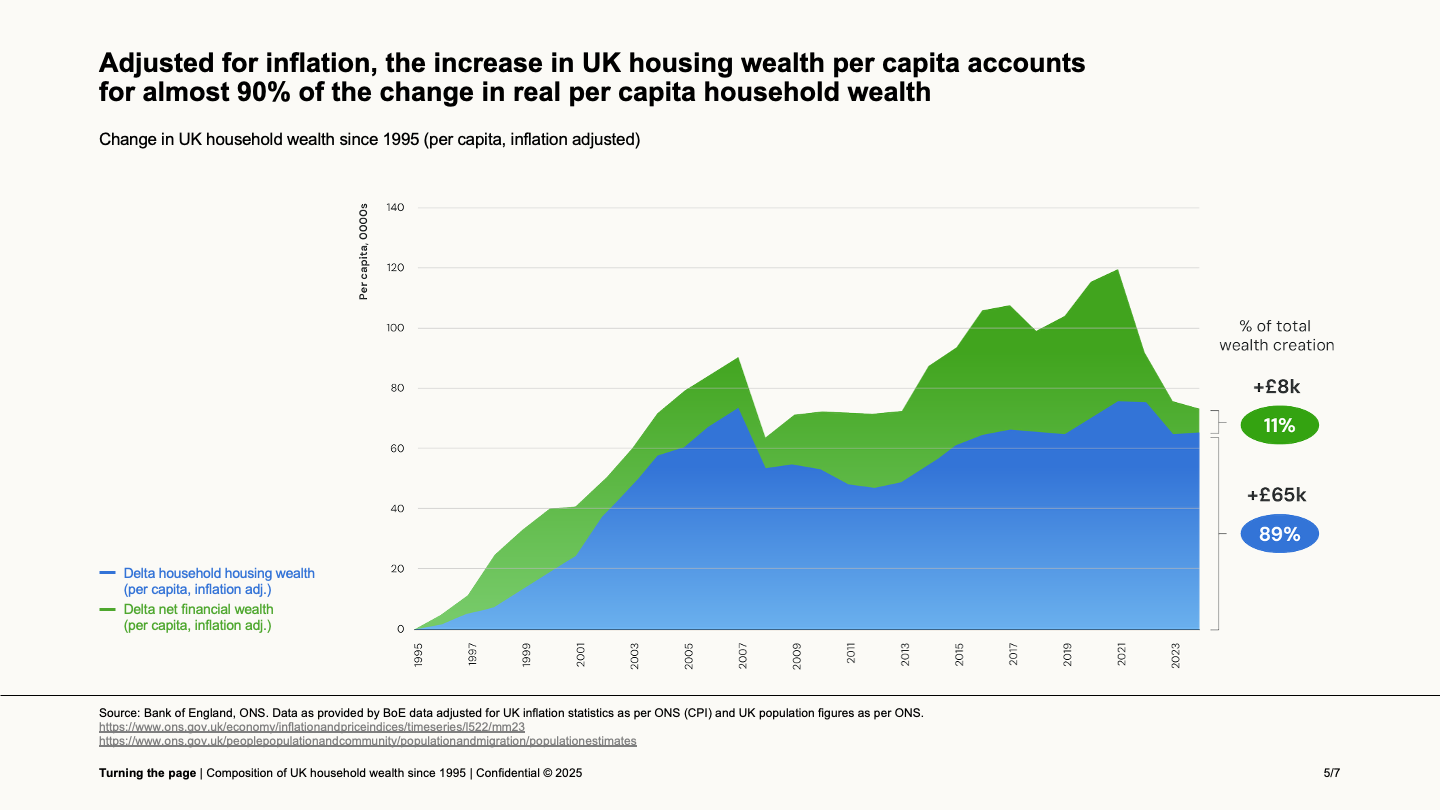

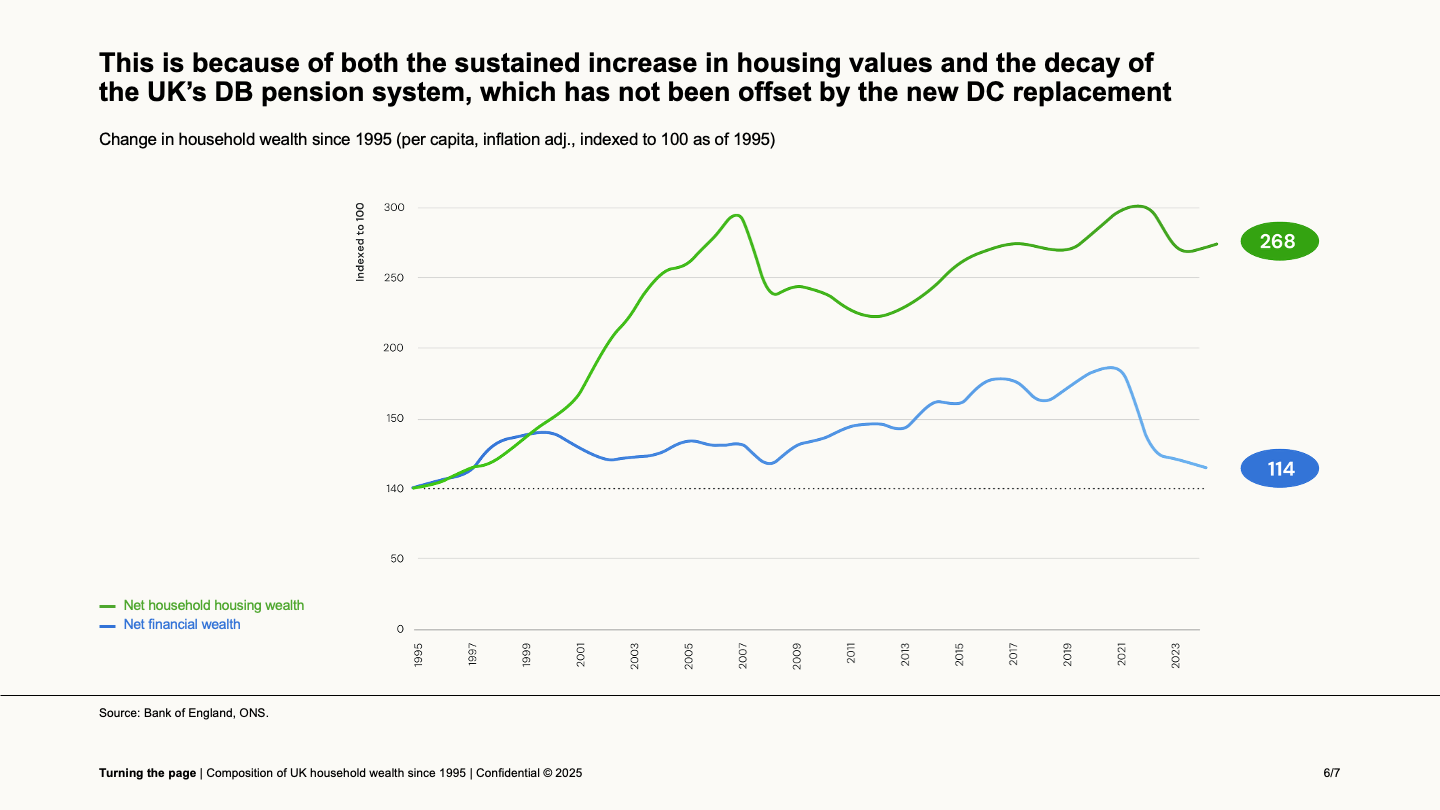

This is not what has been happening in the UK over the past thirty plus years. In particular, the vast majority (approaching 90%(1)(2)) of the change in real per capita national wealth over this period has been from the increased value of housing, with negligible real per capita wealth creation from financial assets; UK real estate wealth is now 1.6 times the nation’s financial wealth, compared to just 0.6 times in the US(3).

Main drivers

This evolution has two main drivers, the first of which is Personal Residence Relief (PRR), under which gains on the sale of a primary residence are exempt from capital gains tax (CGT). This tax bias is on top of the underlying supply demand imbalance – namely a decades long shortage of new housing combined with an increasing population – which is further magnified by the relative ease of obtaining debt secured on property compared to business loans.

These factors have, with bipartisan political backing, made housing overwhelmingly the most attractive, lowest risk, tax advantaged investment that the vast majority of the UK population can make.

The first driver has then been compounded by the second, namely the destruction in the early 2000s of the UK’s defined benefit pension system and the total inadequacy of its replacement, leaving 88% of today’s savers with less than what they need to live comfortably in retirement(4).

Housing wealth instead of pensions

Housing wealth has, as a consequence, become for most people their tax free retirement fund, filling the void left by the collapse of the pension system and its woefully inadequate successor, which is plainly visible in the decoupling of the value trajectories of housing and financial assets in the period following the demise of the private pension system in 2004/5(5).

Thus, rather than being a peculiar UK cultural phenomenon, the tax bias to real estate has combined with a justified fear of post-retirement poverty to make concentrated investment in residential property an entirely rational individual decision.

Why does this matter?

How is this all connected to wealth creation and economic growth?

Take the limit case where 100% of a country’s domestic wealth is in real estate, and all of the capital required to fund everything that is not real estate (new business formation, capital expenditure, infrastructure etc) is sourced from abroad.

In this case, individual lifetime wealth creation would be capped at the increased value of their housing plus after tax wages from employment, while the infinite wealth generated from the UK’s unmatched creativity, innovation and business profits and dividends would flow entirely to foreign savers, who would accumulate the wealth we have relinquished here.

In this scenario, the country’s entire domestic capital is locked up in real estate and unavailable for re-circulation and investment in the real economy, while only a fraction of the wealth leakage returns as new investment, hence why the UK’s dependence on foreign capital can never make up for the practical absence of the domestic saver.

Overconcentration of wealth in housing is choking off economic growth

This is the direct link between: the UK’s misallocated capital, the lack of compounded financial wealth for retirement savings, and the shortage of domestic capital and savings for investment to drive economic growth and productivity. And this is not theoretical: at the past thirty years’ rates of wealth accumulation, in just two decades more than three quarters of the UK’s per capita household wealth will be in real estate(6).

This is the unsustainable path the UK finds itself on today: a pattern of capital misallocation that has coincided with almost two decades of zero per capita income growth and a massive generational injustice, with the over 60s owning more than half (56%)(7) of total housing wealth today and those under 45 left with the tragic distinction of being the first generation since the Industrial Revolution to live less well than their parents.

What is to be done?

There are two pieces of good news: first, a main plank of the fix is straightforward – level the playing field between the tax incentives for investing in housing and for all other domestic investment. This would entail either abolishing or drastically curtailing PRR, with a credit against inheritance tax payable for CGT already paid on property sales.

The Treasury estimates that this privilege results in a staggering £30 billion per year of tax revenue forgone – the UK’s single most expensive tax subsidy(8). Eliminating or curtailing PRR would create scope to facilitate a long overdue rebalancing of the UK’s capital allocation towards productive investment, for example in the region of £15 billion (depending on the behavioural response) of potential fiscal flexibility.

How to begin capital redeployment

The first re-deployment should be a ‘twofer’: incentives to favour investment in UK productive assets which are in turn set aside to fund long term retirement savings, for example a step change – say up to 20% – of an individual’s total income in tax free contributions to ISAs compared with the present limit of just £20,000 – with at least 50% of the increased contribution to be invested in UK productive assets and eliminating completely the tax privilege accorded to investing into cash ISAs, especially as so much of this cash ends up, via the building societies, invested in real estate.

Beyond the increased incentives to invest productively through ISAs, there would also be a lifetime CGT exemption for any qualifying investment in the equity of a private UK business.

Further, to encourage and facilitate capital reallocation to financial assets, especially public equities, eliminate stamp duty on share transactions, absorbing £3 billion per annum(9).

Finally, up to £7.5bn per annum to begin making up for the past two decades’ negligent erosion of our national security. This would cover almost half of the uplift from 2.5-3%, the Government’s currently unfunded defence spending aspiration; without something like this change to PRR, meeting the defence spending increase would entail painful choices and cuts. Publicly underpinning an increase of this magnitude would also show the way for our allies and send a strong signal of resolve to adversaries.

Why this needs to be addressed and why now

This levelling of the playing field would advance multiple policy goals – a wholesale rebalancing of the UK’s capital allocation from housing to productive domestic assets to drive investment led growth and productivity, begin recapturing for our own citizens the wealth and value generated in our own country, and last but not least reinforce our vital national security.

Moreover, extinguishing the tax bias presently inflating housing values would also over time start to bring the purchase of a home back into reach for an entire excluded generation that, even with two incomes, simply cannot afford to buy a home, one of the biggest and justified sources of social discontent and immobility in this country today.

With everything in flux in the global environment, this must surely be the moment once and for all to address a previously untouchable and suffocating distortion, if only to restore faith amongst the younger generations who have borne the brunt of the last two decades of economic stagnation and to create hope for a brighter, more prosperous and more secure future.